Softwoods

Learn More

With approximately 2,800 species worldwide, palm trees are iconic plants of tropical, subtropical, and frost-free temperate regions. They feed millions of people, anchor coastal and oasis ecosystems, and are widely planted to enhance the beauty of landscapes and resorts.

The fossil record shows that palms have been around for more than 60 million years, making them some of the oldest fruit-bearing plants still in cultivation. Date palms in particular were instrumental in early human migration across the Middle East, North Africa, and into Europe, providing food, shade, building materials, and trade goods along desert caravan routes.

Palm trees are neither hardwood nor softwood in the traditional sense. Botanically, palms are giant monocot grasses (like sugarcane, bamboo, corn, and rice), not true woody trees. Instead of annual growth rings and solid heartwood, they are made up of fibrous, vascular bundles embedded in softer tissue.

Because of this structure, palms do not produce conventional lumber. However, innovative processing can turn palm trunks into dense, wood-like material. A pioneering Japanese scientist developed a method of compressing the fibrous stalk into hard, dimensionally stable blocks that can be sawn and milled much like hardwood.

“Palm wood” is created by compressing the stalk-like fibers of the trunk under high pressure to form dense blocks, which can then be milled into dimensional lumber. The more compression applied, the darker and denser the finished product becomes. For example, Red Palm is lighter and about half as dense as Black Palm, which is heavily compressed.

While engineered palm wood is not typically used for major structural beams, it is an attractive, sustainable material for smaller projects: natural, organic-looking utensils, bowls, cups, furniture, flooring, paneling, and woven décor. It allows communities to derive value from palms beyond fruit production, especially when trees are removed from urban or plantation settings.

Around the globe, countries are racing to slow or reverse desertification—the process by which fertile land degrades into desert. Today, this creeping land degradation affects roughly one-third of the world’s population, undermining food security and livelihoods.

In China, large-scale tree planting campaigns aim to halt the expansion of deserts in the north and west. In Africa, a multi-nation effort is building the “Great Green Wall,” a band of trees and vegetation stretching across the continent to slow the advance of Sahara sands, which can consume hundreds of acres of usable land every day.

In the Middle East, the UAE is also addressing desertification by planting long walls of trees along vulnerable borders, using hardy species that can withstand heat, wind, and sand.

History suggests that it can. In 1935, overgrazing and drought caused approximately 850 million tons of topsoil to blow off the U.S. southern plains, leaving millions of acres barren and creating the Dust Bowl. To combat this, the newly formed Soil Conservation Service launched the Shelterbelt Project—planting a 100-mile-wide strip of native trees stretching from Canada to Texas. Within a few years, airborne soil was reduced by roughly 60%.

Today, similar “living barriers” can be created using climate-resilient species and advanced propagation technology. Planting a wide wall of 12- to 15-foot tree saplings with deep, well-developed root systems can anchor soil, slow wind, and dramatically reduce the layering of windblown sand in desert environments.

Palm trees—especially date palms—are powerful tools for reclaiming desert margins. They tolerate intense heat, wind, and drought, provide shade, stabilize soil, and supply food at the same time. As native or well-adapted species in many arid regions, they fit naturally into oasis-style agroforestry systems.

An acre of date palms can sequester approximately 10 tons of carbon annually, comparable to many temperate hardwoods, while also creating a cool, moist microclimate that supports under-story crops, people, and wildlife.

How Palm Trees Capture and Store Carbon:

Date palms are often called the “tree of life” for their cultural, spiritual, and practical importance. In many accounts they are considered among the oldest cultivated fruit-bearing trees on Earth.

Food: Date palms provide highly nutritious fruit, seeds, and sap that have sustained desert cultures for millennia.

Shelter & materials: Leaves, midribs, and trunks are used for thatch, mats, baskets, fencing, and simple structures.

Medicine & wellness: Traditional remedies use palm oils, saps, and pollen for a variety of ailments.

Spiritual significance: Palms appear in religious texts and ceremonies across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, symbolizing victory, peace, and eternal life.

Economic value: Date production, palm fiber products, and palm-derived oils form the backbone of many local economies in arid regions.

While most palms prefer tropical or subtropical climates, several species are surprisingly cold hardy and can be grown in temperate regions with proper siting and protection. These “hardy palms” tolerate freezing temperatures and even occasional snow.

In marginal climates, careful site selection (south-facing walls, reflected heat, wind protection) and winter protection can make the difference between success and failure with hardy palms.

Separated by vast oceans and continents, palms have evolved into some of the most remarkable plants on Earth. The legendary Coco de mer of the Seychelles produces the largest seed in the plant kingdom—up to 20 inches across and weighing more than 40 pounds. In contrast, the wax palm, Colombia’s national tree, is the tallest palm in the world, reaching heights of over 300 feet.

Two thousand years ago, dense groves of Judean date palms thrived in the Jordan River Valley. Roman campaigns and land-use changes led to their disappearance, and for centuries the trees were thought to be lost.

Recently, seeds of the ancient Judean Date Palm were discovered in a 2,000-year-old food store at Masada, a mountaintop fortress overlooking the Dead Sea. Against all odds, several of these seeds were successfully germinated, setting a record as some of the oldest stored seeds ever to grow into living trees.

As these revived palms mature and begin to bear fruit, interest is growing in reintroducing this historic variety to the region as both a cultural symbol and a living genetic resource.

Palm oil has long been valued for its culinary and medicinal uses. It is naturally rich in vitamin E compounds and carotenoids, and in some traditions palm oil extracts are used as anti-inflammatories or to help ease coughs and throat irritation. Dates, produced within many of the same palm-based oasis systems, are packed with vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, A, and C, plus fiber, calcium, iron, phosphorus, sulfur, potassium, copper, magnesium, and manganese. They are best eaten raw, either fresh or dried, to retain their full nutritional value.

Commercial palm oil comes from the fruit of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), native to West and Southwest Africa but now grown widely in Southeast Asia, South America, and equatorial Africa. The oil palm is an extraordinarily productive crop—capable of yielding many times more oil per acre than other oilseed crops—making it an efficient source of vegetable oil for food, cosmetics, soaps, and even biofuels.

However, large-scale palm oil expansion has also been linked to deforestation and peatland draining in some regions. The future of palm oil depends on responsible, certified production and reforestation of degraded land rather than conversion of intact forests.

One innovative concept in the Middle East imagines transforming a portion of the Oman desert into a regenerative “green dot.” This thousand-acre oasis design centers on thousands of date palms that shade the soil, produce valuable fruit, and sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

A three-mile-long covered archway shields the system from blowing sands, while enclosing:

Projects like this demonstrate how palm trees can anchor circular, climate-smart agriculture in some of the harshest environments on Earth.

Partner with us in a land management project that repurposes fallow or low-value agricultural lands into appreciating tree assets. Tree Plantation has partnered with Growing to Give , a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, to create long-term tree planting partnerships with land donors.

Together with Growing to Give , we’ve created a land-and-tree partnership program that turns idle acreage into productive forests.

The model is simple: you own the land and you own the trees we plant for free. There are no program entry costs and no restrictive covenants—you are free to sell or transfer the land with the trees at any time.

If you have 100 acres or more of relatively flat, fallow land and would like to explore planting trees for long-term value and climate impact, we would like to talk to you.

Botanically, palm trees are neither hardwood nor softwood. They are giant monocot grasses, more closely related to sugarcane and bamboo than to true trees. Instead of annual growth rings and solid heartwood, palm “trunks” are made of fibrous vascular bundles embedded in softer tissue.

Because of this structure, palms don’t yield conventional lumber. However, when the fibrous stems are compressed under high pressure, they can be turned into dense, engineered “palm wood” that mills and finishes much like hardwood and works well for bowls, utensils, furniture and paneling.

Palm trees, especially date palms, are powerful tools for slowing desertification. Planted in belts or shelterbelts, palms slow the wind, trap blowing sand, shade the soil and create cooler, moister microclimates at the desert’s edge. This protects cropland, villages and infrastructure from creeping sand.

Historic projects like the Dust Bowl-era shelterbelts in the United States, and modern “green wall” initiatives in Africa, the Middle East and China, show how long walls of trees can reduce erosion and help reclaim degraded land when combined with good land management.

Like all green plants, palms capture carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and lock it away in their trunks, fronds and roots. As palms grow, this living biomass becomes an expanding carbon store. An acre of date palms can sequester carbon at rates comparable to many temperate hardwood stands.

Over time, falling fronds, root turnover and organic litter build carbon-rich soils beneath palm groves. This below-ground carbon store improves soil structure, boosts fertility and increases water-holding capacity—key advantages for oasis agriculture and desert-margin farms.

Used correctly, yes. A wide, dense wall of palms and other hardy trees can function as a living barrier that slows wind speeds and reduces the amount of sand carried across the landscape. Deep, well-developed root systems help anchor soil, while the shaded microclimate reduces evaporation.

When integrated into larger agroforestry systems with shrubs, groundcovers and crops, palm shelterbelts can turn bare sand into productive “green dots” that support food production, livestock and local communities along the desert fringe.

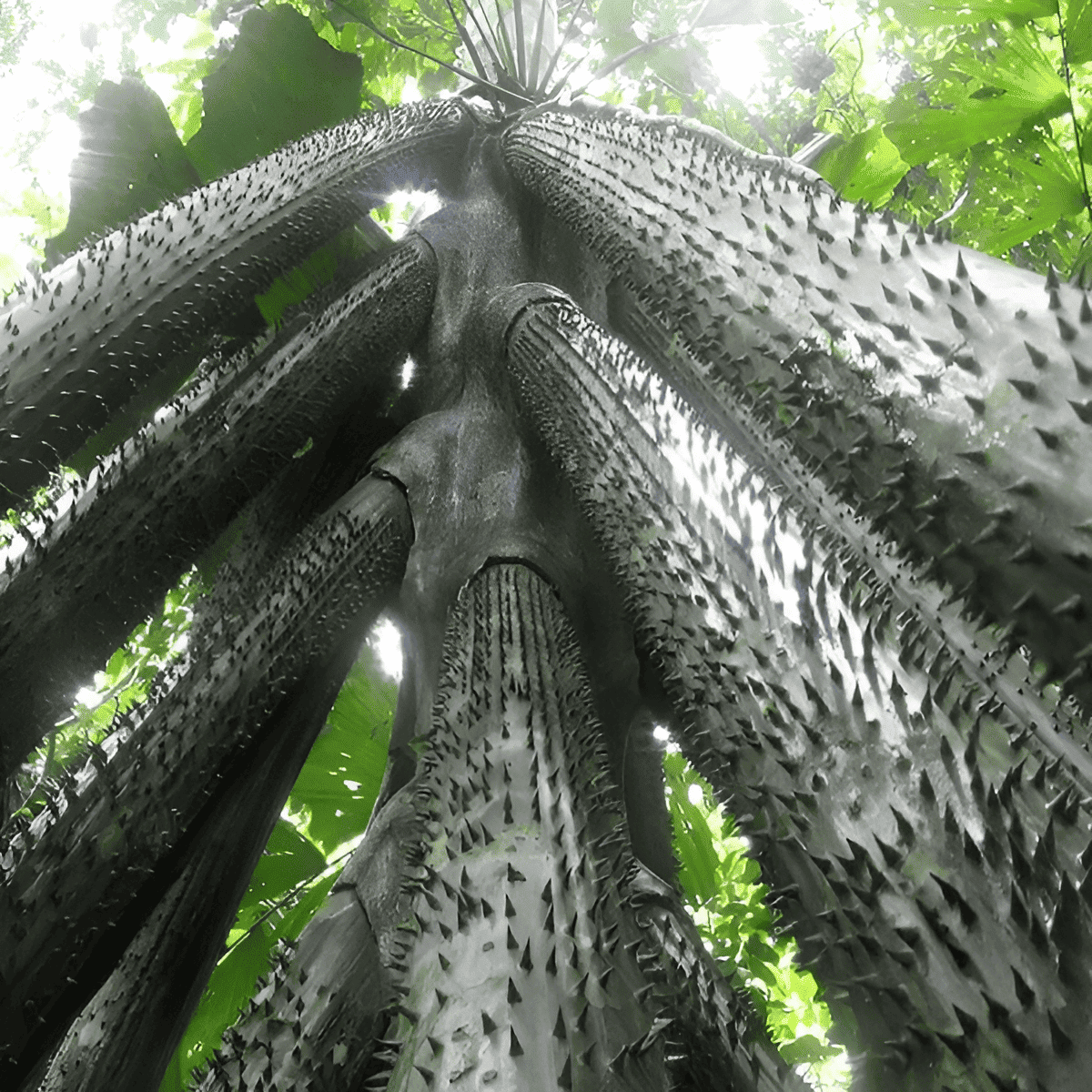

Most palms are native to tropical or subtropical regions, but several hardy palm species cope well with freezing temperatures and even occasional snow. Examples include European fan palm (Chamaerops humilis), windmill palm (Trachycarpus fortunei), needle palm (Rhapidophyllum hystrix) and dwarf palmetto (Sabal minor).

Success in temperate gardens depends on choosing cold-tolerant species, providing fast-draining soil, and using heat-reflecting walls, windbreaks and winter protection during the coldest snaps. In favorable coastal or urban microclimates, hardy palms can give landscapes a distinctly “subtropical” feel far from the tropics.

The Judean date palm is an ancient date variety that once formed dense groves in the Jordan River Valley. It was famous in historical and religious texts for its fruit quality and symbolic value, but it disappeared centuries ago due to war, overuse and land-use change.

In a remarkable feat of conservation, seeds recovered from 2,000-year-old storage sites such as Masada were recently germinated, bringing this “extinct” palm back as living trees. The Judean date palm now stands as a symbol of biological resilience, cultural heritage and the potential to revive lost genetic resources for future agriculture.

Engineered palm wood, created by compressing the fibrous trunk, is best suited to small, high-value projects rather than heavy structural beams. Its striking grain and color variations work well for bowls, cups, utensils, tabletops, furniture accents, wall paneling and decorative elements in eco-resorts and homes.

Because many palms are removed from urban streets, old plantations or storm-damaged sites, turning stalks into palm wood products can add value to what would otherwise be waste, supporting circular, low-waste uses of palms beyond fruit and oil production.

In traditional oasis agriculture, date palms form the upper canopy, casting dappled shade over citrus, pomegranates, figs and other fruit trees, with vegetables and forage crops grown underneath. This multi-layer system makes efficient use of limited water and land while buffering crops from extreme heat and wind.

Modern “green dot” projects expand on this idea, combining date palms with protected irrigation canals, fish ponds and vegetable beds to create regenerative hubs of food production, jobs and carbon storage at the edge of expanding deserts.

Palm oil itself is highly productive per acre and has long been used for food, medicine and soap. Problems arise when new plantations replace high-biodiversity rainforests or peatlands. In those cases, the climate and wildlife costs can outweigh the benefits of the oil.

More responsible models prioritize growing oil palms on already-cleared or degraded land, protecting remaining native forests, and improving yields on existing plantations. As a consumer, looking for palm-containing products that reference certified or sustainable sourcing is one way to support better practices.

You can support palm-centered restoration by backing initiatives that use date palms and other resilient species to reclaim deserts, stabilize coastlines and improve food security. Programs that integrate palms into reforestation and climate-smart agriculture, or that help smallholders plant diversified palm-based agroforestry systems, provide both ecological and economic wins.

Learning more about tree-based carbon sequestration, choosing products that respect forests, and sharing the story of palms as “trees of life” in drylands all help build momentum for projects that use palm trees to cool the planet while feeding people.

Copyright © All rights reserved Tree Plantation