Softwoods

Learn More

Willow trees (Salix species) are versatile, fast-growing softwoods native to wetlands and riparian areas, yet many varieties adapt well to a wide range of soils and temperate climates. They are one of the few tree groups that can generate value across multiple markets at once—timber, biomass, land restoration, windbreaks, and even natural medicine—making them a powerful choice for landowners, smallholders, and commercial tree plantations.

From a forestry perspective, willow trees are ideal for short-rotation coppice systems, agroforestry projects, and bioenergy crops. Their combination of rapid growth, strong coppicing ability, and high water use makes them especially useful on wet, low-value land that is too saturated for traditional crops. In addition, willows provide habitat, shade, and erosion control along streams, lakes, and drainage ditches, improving both land productivity and environmental health.

Well-managed willow plantations can generate multiple income streams and ecosystem services from the same acreage. Key uses include:

Estimate biomass yield, harvest cycles, coppicing performance, and per-acre profitability across multiple tree species and climate regions. Compare dry vs green tons and model short-rotation biomass systems with confidence.

Willow trees are easily recognized by their characteristic hanging branches that create a sweeping, inverted half-circle canopy. They are commonly found along riverbanks, lake shores, drainage channels, and wetlands, where they play a vital role in regulating water tables and stabilizing soils. Because of their high water demand, willow trees are generally unsuitable for arid, low-rainfall climates unless irrigated.

With a growth rate of about 3 feet of branch growth annually—and often more in prime sites—willows are naturally short-trunked due to early branching close to the ground. While this makes wild trees less suited to long sawlogs, targeted pruning and plantation design can turn willow into a surprisingly capable commercial timber species.

In commercial plantations, tree species are chosen to produce long, straight sawlogs for pole wood and milling. Willow’s excellent workability and attractive light-to-dark stain appearance make it a useful “utility hardwood” in markets that value speed of growth and easy machining. Plantations perform best in water-rich environments—wetlands, low-lying fields, and riparian zones—where waterlogging would reduce yields in other species.

Willow seedlings are inexpensive, and seeds or cuttings are easy to germinate and establish in water-soaked soils. Many growers propagate willow from dormant cuttings pushed directly into moist ground, reducing nursery costs dramatically. Once established, willow trees rapidly form dense stands that can be managed either for long sawlogs, short-rotation biomass, or a combination of both.

To grow long, branch-free willow sawlogs, regular pruning is essential. Each spring, lateral branches are removed from the main vertical stem, leaving a slender “whip” to grow throughout the season. This training is repeated annually for five years or until the tree reaches a height of 20–25 feet, at which point the stem begins to thicken into a high-value log.

Over time, these trained whips develop into tall, straight sawlogs with impressive trunk diameters and clear, knot-free wood—ideal for veneer, specialty timber, and high-grade boards. Plantations can be laid out using the tree spacing calculator to optimize row spacing for machinery access, pruning, and future harvesting.

White willow (Salix alba) is the preferred species for timber production due to its superior stem form, fast growth, and light-colored wood. In some regions, local willow hybrids and selected cultivars may outperform wild types. For craft and furniture wood, growers look for straight stems, fine grain, and minimal knots—qualities that intensive pruning and good spacing can provide.

Managed correctly, willow plantations can yield high-quality timber while capitalizing on the natural growth characteristics of this remarkable tree. In mixed forestry systems, willow can serve as a nurse species, providing early income and shelter for slower-growing hardwoods such as black walnut, oaks, or maples.

Use the free tree value calculator to estimate the potential dollar value of mature willow trees on your woodlot or farm, taking into account trunk diameter, height, and log quality.

Willow trees hold immense potential as a source of biomass, particularly for manufacturing wood chips and pellets used in renewable energy production. Willow biomass is often treated as “carbon-neutral” in many policy frameworks because the carbon released when burned equals the carbon absorbed during rapid regrowth. In practice, short-rotation willow closely behaves like a perennial energy crop rather than a slow-growing timber tree.

This makes willow biomass highly attractive for industrial boilers, district heating systems, and power plants looking to replace or co-fire with fossil fuels. It also creates an opportunity for landowners to participate in carbon-credit and offset projects, especially where willow plantations help reclaim marginal land and protect waterways.

Willow trees are among the most effective coppicing species on the planet. After the first harvest, cut stumps send up multiple fast-growing shoots, turning a single trunk into a clump of vigorous stems.

This coppicing ability dramatically increases long-term biomass yields and shortens subsequent harvest cycles by approximately one year. Unlike traditional plantations that require wide spacing to grow large trunk wood, willow biomass plantations are planted densely, with trees spaced about 5 feet apart in both rows and between rows. The result is a thick, almost impenetrable hedge optimized for maximum biomass production.

Weeping willow (Salix babylonica and related hybrids) is a preferred species in many biomass projects due to its superior growth and coppicing characteristics. Other specialized willow hybrids bred specifically for bioenergy can also be used, depending on regional availability.

Willow trees are poised to become an industry favorite because you only need to plant once and harvest for life—a compelling model for farmers and landowners seeking low-input, long-term biomass supply.

Willow trees are highly effective for land reclamation, especially in low-lying wetlands, floodplains, and areas with little agricultural value. Their high water consumption can lower water tables by several feet, reclaiming portions of land for grazing or cropping while reducing standing water and nuisance flooding.

With extensive, fibrous root systems, willows stabilize slopes along washouts, ravines, and riverbanks. They quickly rebuild ecosystems—often within three to five years—providing shade, organic matter, and habitat while their roots extract pollutants and excess nutrients from water and soil.

Willows are particularly useful in restoring degraded lands such as old mine tailings, open-pit excavations, or industrial buffer zones. As part of a reforestation or phytoremediation strategy, willow roots can absorb and immobilize some heavy metals and contaminants, storing them in the wood and foliage. Once harvested, contaminated biomass must be managed responsibly, but the site is left more stable and biologically active.

Willow trees are an excellent choice for windbreaks because they leaf out quickly in spring, build dense crowns, and significantly reduce wind speeds—often by up to 70% on the leeward side of the shelterbelt. This protects crops, livestock, buildings, and homes from wind damage and desiccation.

Willow windbreaks offer additional benefits beyond wind control:

Using the windbreak calculator, you can model optimal spacing, number of rows, and tree density for your property, whether you are protecting a homestead, pasture, or commercial crop field.

Willow bark has been used medicinally for centuries. Many Indigenous cultures and traditional healers have relied on its bark, which contains salicin—a natural compound related to the active ingredient in aspirin—for relief of headaches, muscle pain, joint pain, and fever.

In addition to its analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, willow bark is mildly antiseptic and antifungal, making it useful in traditional remedies for minor infections and skin issues. Modern herbalists still employ willow bark teas, tinctures, and extracts, although anyone using it regularly should consult a qualified healthcare professional, especially if they are already taking blood thinners or aspirin-based medication.

Willow wood plantations offer a unique opportunity to create multiple revenue streams from a single land base. Branches too small for pellet production can be harvested for their medicinal bark, dried, and sold into herbal or nutraceutical markets. Larger stems can be processed into chips, pellets, or craft lumber.

By integrating timber, biomass, and medicinal bark production, willow growers can diversify their income, spread risk, and increase the overall value of their plantations—especially when combined with land-credit programs, carbon offsets, and ecosystem service payments.

Design effective willow windbreaks, shelterbelts, and living fences by using the windbreak calculator to determine spacing, row layout, and expected protection zones.

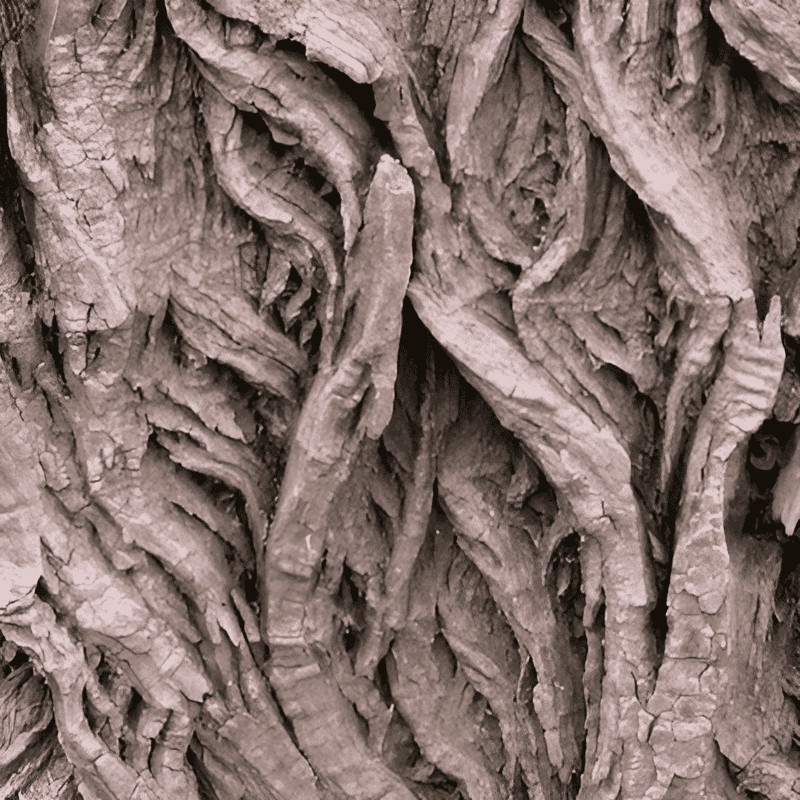

Willow wood is a soft, lightweight material with a straight grain and a pale yellow to creamy white hue. Known for its remarkable flexibility and shock resistance, it is widely used in crafting baskets, bentwood furniture, tool handles, sporting goods, and other woven or shaped items.

Although not particularly hard or decay-resistant, willow’s easy machining makes it ideal for indoor applications, turned items, carving, and utility furniture. It is less suited for ground-contact or heavy structural use, where durable species such as western red cedar or Douglas fir are preferred.

Abundant and widely available, willow wood is a cost-effective choice for commercial uses such as furniture components, pallet stock, crate lumber, and basketry. Its affordability and versatility also make it a favorite among DIY enthusiasts and hobby woodworkers for a wide range of projects—from garden structures and trellises to indoor décor.

Panel doors use a frame-and-panel construction with stiles, rails, and floating panels, giving them a classic, detailed look. Flush doors have a smooth, flat surface made from skins over a solid or hollow core, ideal for modern and minimalist interiors. Louvered doors include angled slats that let air pass through, making them perfect for closets, utility rooms, and spaces that need ventilation.

For bedrooms and living areas, solid-core panel or flush doors are usually the best choice. Solid-core construction helps with sound control and creates a more substantial feel when opening and closing the door. Shaker-style panel doors work well in both traditional and modern homes, while flush doors suit contemporary and mid-century interiors.

Exterior wood doors should be thicker, weather-sealed, and made from durable species such as oak, mahogany, or properly treated softwoods. Look for features like insulated glass, quality weatherstripping, an adjustable sill, and a high-performance exterior finish with UV protection. A roof overhang or storm door will significantly extend the life of a wood entry door.

Solid wood doors offer a premium feel, long service life, and can be refinished multiple times, but they cost more and can move with seasonal humidity if not sealed correctly. Engineered and solid-core doors use layered or composite cores for improved stability and a lower price point while still providing good weight and sound damping. For many homes, solid-core engineered doors are an ideal balance between performance and budget.

Choose the species that fits your style and performance needs:

Use louvered doors anywhere air flow matters: closets, laundry rooms, mechanical rooms, pantries, and linen cupboards. The angled slats help prevent stale odors, let equipment shed heat and humidity, and can meet ventilation requirements for furnaces or water heaters while still providing privacy.

For better noise control, choose a solid-core or solid wood door instead of hollow-core, and pair it with continuous weatherstripping around the frame. Add a quality door sweep and solid threshold at the bottom to block sound leaks. In sensitive rooms like home offices, media rooms, or nurseries, sealing small gaps in the casing and using soft furnishings or acoustic panels in the room will further reduce noise.

For interior doors, occasional dusting and gentle cleaning with a damp cloth are usually enough. Exterior doors need more attention: keep all edges sealed (including the top and bottom), inspect the finish annually, and re-coat with an exterior-grade paint or clear finish when it begins to dull or crack. Avoid harsh cleaners and standing water, and make sure hardware is adjusted so the door closes smoothly without rubbing or binding.

Yes—many homes successfully mix styles as long as there is a coherent overall theme. For example, you might use panel doors for main living areas, flush doors for closets, and louvered doors for laundry and utility spaces, all finished in the same color family. Keeping hardware and trim consistent is the easiest way to tie different door types together visually.

Softwoods, the pioneer species of the temperate forest, grow quickly to leave their mark on the landscape for centuries. Many, like willow, can be planted in short-rotation systems that generate timber, biomass, and ecosystem services in a single rotation.

Explore each species page to compare growth rates, wood properties, and potential returns from tree plantations designed for timber, biomass, and carbon.

Partner with us in a land management project to repurpose agricultural lands into appreciating tree assets. We have partnered with Growing to Give , a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, to create tree-planting partnerships with land donors. Together, we can establish willow and mixed-species plantations that restore soil, protect water, and generate long-term value.

We have partnered with Growing to Give , a Washington State nonprofit, to create a land and tree partnership program that repurposes agricultural land into appreciating tree assets.

The program utilizes privately owned land to plant trees that benefit both the landowner and the environment—combining income potential from timber or biomass with measurable ecological gains.

If you have 100 acres or more of flat, fallow farmland and would like to plant trees, then we would like to talk to you. There are no costs to enter the program. You own the land; you own the trees we plant for free, and there are no restrictions; you can sell or transfer the land with the trees anytime.

Copyright © All rights reserved Tree Plantation